The Journey of a Student Mountaineer

- doctoralresearcher

- Jun 25, 2021

- 3 min read

James Iain Sword describes his mountain adventures inspired by his time at Strathclyde.

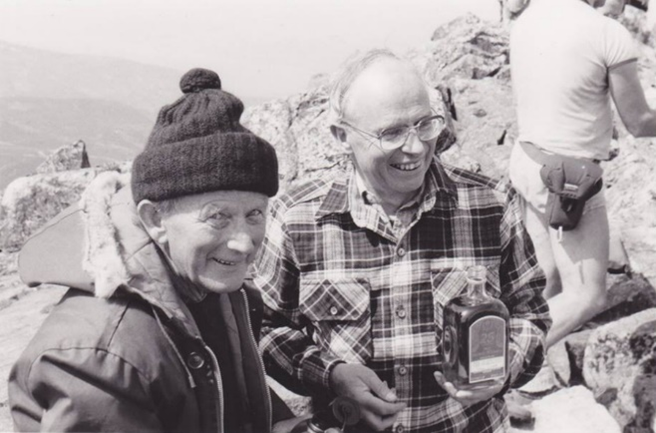

It’d be quite easy to say that I come from a family of mountaineers and adventurers. Both my dad and grandpa completed all 282 Munros (with grandpa doing the supplemental 227 summits!). The Munros are those mountains in Scotland which are over 3000 feet high. My dad also competes in mountain bike races in Scotland and abroad, and a great uncle moved to Fiji when, while serving as a ships engineer, he decided to “get off” and settle down starting a Pan-Pacific line of the Sword family.

I spent a great deal of my childhood (willingly and unwillingly) going up hills, bombing around on mountain bikes and visiting the Western Isles. I then went through a terrible teen phase where I hated anything to do with the outdoors, mildly tempered by a brief stint doing that rite of passage for British middle class teens: Duke of Edinburgh Award, a few stomps round the Cairngroms getting soaked to the bone later and I never wanted to see a hill ever again.

All that changed with my first year at Strathclyde.I was a recluse but made a few friends, who then convinced me to walk the West Highland Way and I spent over a week hearing tales of helicopter airlifts, exciting climbs and fun and games taking place in village halls. After that, I became sure thatI was going to get back into hills and adventure. All it had taken was a pleasant experience with the right people.

So, come September, I joined SUMC, Strathclyde University Mountaineering Club, learned to climb, and went on a few weekend trips to a great deal of excitement and some tall tales of my own. I would spend my weekends in Glasgow Climbing Centre with some exchange students and we hosted a St. Andrews day party which was great fun. That summer I learned the new challenge of “trad climbing” – outdoor climbing where you carry your protective equipment with you, and attach yourself to the cliff with lumps of metal and nylon slings.

The next challenge was winter walking, and eventually climbing! This was a big step- up from anything I’d done before. It involved ice axes, crampons (metal shoe spikes) and a drastically overweight rucksack carrying clothes, food and perhaps ropes. On anything steep, your feeling of security becomes very much defined by the conditions and your own skill. So, the learning curve becomes steep.

Lethal accidents are common in even well-trodden areas like Ben Nevis.

After being shown how things were done by others who had been in the club before me, I decided I would take a more active role when I started my PhD last year. I just got re-elected as safety officer for my second year and have been helping to introduce people to all kinds of climbing as well as organising courses in first aid.

What’s next? I’ve become enamoured with expeditions again as well as more adventurous trips such as alpine climbs, where sleeping on the summit in a waterproof sleeping bag is common. As well as this, I’ve become involved in polar science through the British Antarctic Survey and aspire to work as a field guide. To achieve that, I’d better get climbing!

Author’s note:

As of writing this, I’m just back from an attempt to climb some ice on Ben Nevis with a friend made on a polar research course. Sadly, the weather conditions made it unsafe to ascend past the snowline. So, we bravely returned to our tent and cooked lunch. I found it an excellent reminder of the old adage: “discretion is the better part of valour..” Safety comes first, and the fun can be found wherever you look for it. Ultimately, the true enjoyment of mountaineering is a combination of the right place, the right activity, and the right people.

Author retains copyright for all text and images.

Comments